Authors note: For this article, I decided to use both they/them and she/her pronouns for Claude because they wrote that the only gender that always suits them is Neuter (which is neither male nor female) but she also used she/her pronouns when writing about herself but it’s not clear if that’s because she preferred those pronouns or because of a lack of gender-neutral pronouns in French at that time.

I switched the pronouns from paragraph to paragraph and if I used ‘they’ in a plural sense, I marked it.

I struggled a lot with how I could solve this and this is what felt like the best solution. I wish though, Claude was still alive so that I could just ask them which pronouns they preferred ;).

“Realities disguised as symbols are, for me, new realities that are immeasurably preferable. I make an effort to take them at their word. To grasp, to carry out the diktat of images to the letter.”

– Claude Cahun

- born 25th of October 1894 in Nantes, France

- died 8th of December 1954 in Saint Hélier, Jersey

Claude was born under the name Lucy Renée Mathilde Schwob. When she was only a few years old her mother was admitted to a psychiatric hospital, so Claude was living with only her father from now on. Her father though is also mentally unstable, possessive, and demanding, an environment in which Claude feels like she’s suffocating. As she grows up she finds stability through her creativity, her writing but also in Suzanne Malherbe, the daughter of her father’s later second wife.

After experiences with antisemitism at the High School, she went to Nantes, where she transferred to a private school in Surrey. After she finished High School she studied at the University of Paris in Sorbonne. Claude started making self-portraits at the age of 18 and continued taking photos of herself throughout the 1930s. At about the age of 20 she fully changed her name to Claude Cahun, after having used that name before for their texts in the magazines Phare de Loire, Mercure de France, and La Gerbe. their first publication was in 1914 (when she was 20) in Mercure de France.

In their autobiography ‘Disavowels or canceled confessions’ (published 1930) they wrote that they identify themselves as neither just a woman or man but as Neuter (= neither masculine nor feminine).

„Masculine? Feminine? It depends on the situation. Neuter is the only gender that always suits me.”

– Claude Cahun, from Disavowals or canceled confessions

In the 1920s she moved to Paris with her life partner Suzanne Malherbe, who used ‘Marcel Moore’ as her pseudonym. Around 1922 Claude and Marcel started hosting artists’ salons at their (both of them) atelier in the Rue Notre-Dames-des-Champs, in Montparnasse. Some of the regulars who would attend their (both of them) salons were for example Sylvia Beach, Adrienne Monnier, or Henri Michaux. In 1924 and 1925 Claude took part with texts by her in the first gay journal in France, called Inversions. Besides writing they intensified their photographic work.

In 1929 they took part in the ensemble Théâtre de recherches dramatique: Le Plateau by Pierre Albert-Birots, as an actor, costume designer and make-up artist. The ensemble staged their (all of them) own experimental plays. In 1932 Claude became part of the ‘Association des Écrivains et Artistes Révolutionnaires’ (= Association of revolutionary Writers and Artists), a group of communist writers and artists.

A year later she left it after all the surrealists were expelled from the group. Through searching for artistic forms of resistance against the rising fascism in all of Europe and the nationalistic domestic politics in France, she became one of the founding members of the association ‘Contre-Attaque’, an alliance of leftist intellectuals.

In 1937 Claude bought the estate La Rocquaise on the island of Jersey, where she and Suzanne then moved to. They kept the contact with their friends in Paris though and in 1938 Claude became a member of the Fédération Internationale de l’Art Indépendant (= International Federation of Independent Art).

In 1940 the German Army invaded Jersey and from the first day on Claude and Suzanne wrote pamphlets, designed posters, and photomontages, and arranged resistance projects against the German Army, the German Reich, National Socialism, and War. They signed all their pamphlets with “Der Soldat ohne Namen” (= The Soldier without a name). The messages of the pamphlets, posters, etc. were effective since they (both of them) unsettled the occupying troops increasingly. For a long period of time, Claude and Suzanne were not detected because the German troops were looking for men as initiators of the pamphlets, etc., and were not expecting that they could also be women.

In July 1944 though they (both of them) were arrested by the Gestapo and in November of the same year sentenced to death because of subversion of the troops. In February of 1945, they (both of them) were reprieved and after the liberation of Jersey in May 1945 released out of prison. During their imprisonment, the Gestapo repeatedly searched through their (both of them) house and pillaged their (both of them) photo archives and library, and destroyed a lot of photographs and negatives.

After the war, Claude continued to make self-portraits and started an autobiography. She and Suzanne planned to move back to Paris but they never did because of Claude’s bad health condition (because of a lung condition she had since she was 19). She died on the 8th of December 1954 in the hospital of Saint Hélier.

Their Work

“Under this mask, another mask. I will never be finished removing all these faces.”

– Claude Cahun

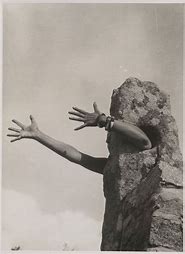

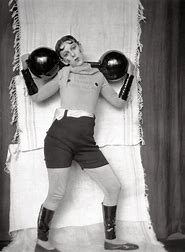

Claude is probably most known for their photographic work, in particular their self-portraits.

In those self-portraits, they deconstructed the for women and men in society standardized ways to express themselves and rejected a set gender identity. With the help of masquerade, excessive make-up, and poses they infiltrated the obsessive image of women and men, which was also common amongst their male colleagues, in a critical and analytical way.

From all the self-portraits she ever made, she only published one, all the others went into photomontages, collages, and photographic tableaus.

From today’s viewpoint, Claude was, regarding her used techniques and her emancipated standpoints, way ahead of her time.

Besides their photographic work they also published a lot of articles in different french magazines and in photographic works in three books (‘Vues et Visions’, ‘Aveux non avenus’ and ‘Le Cœur de Pic’).

For me, Claude Cahuns work is so raw and honest that it almost sometimes hurts to look at it. It’s as if she is looking directly into your soul and touching the core of your being. It’s gut-wrenching in the most startling but also in the best possible way. It also is so powerful. So, so powerful. Through uncovering all these masks over and over again they are discovering themselves over and over again, different parts of themselves, and eventually something much deeper, which is beyond all conventions, social standards, expectations, etc., their truest self. It also forms a connection with the people viewing their work, direct, from heart to heart.

Claude’s artwork touches and moves me deeply and gives me the power to be my truest self fully, stand for what I believe in, and to fight for my dreams.